Why I Believe the Satellite Dish is Doomed, Yet Nilesat Remains King

Mardivsabir

I can still hear that specific, metallic screech. It’s the sound of a rusted satellite dish being twisted on a roof, a noise burned into the sensory memory of nearly every millennial raised in the Middle East or North Africa [1].

I remember scorching afternoons spent shouting down a stairwell to my brother: "Did the signal bar turn green yet?"

"Left! No, go back, you lost it!" he’d scream back.

It was a frustrating, sweaty ritual, but it was our portal to the world. That concave white metal brought us the World Cup, Ramadan marathons, and occasional glimpses into forbidden foreign cultures [2].

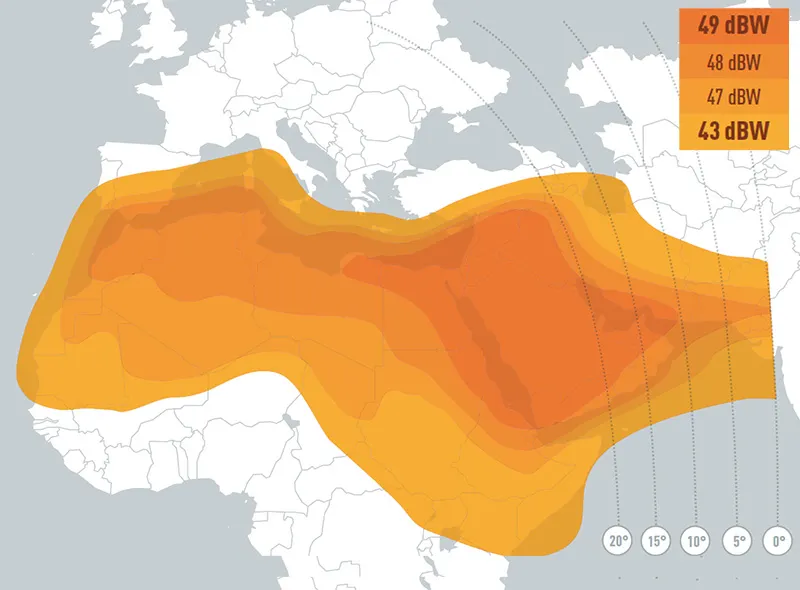

Recently, I stood on that same roof. Looking out at the "dish forest"—a graveyard of metal all pointing uniformly toward 7 degrees West—I felt a wave of obsolescence [3]. I pulled out my phone and streamed a show in 4K without pointing anything at the sky.

It hit me then: classic TV satellites are zombie technology. They are walking dead. Yet, when I look at the data, I’m forced to hold two contradictory thoughts: the tech is dying, yet in the Arab world, Nilesat and Arabsat are thriving in defiance of global trends [4].

The Global Death of Linear TV

Personally, I haven't voluntarily watched a linear broadcast in three years. The idea of "appointment viewing"—needing to be on the couch at 9:00 PM—feels as archaic as using a rotary phone [5]. The world has moved to on-demand. I want what I want, when I want it.

In the US and Europe, "cord-cutting" is decimating the industry. Satellites are being relegated to data transmission rather than broadcasting [6]. Why tolerate signal blackouts during rain when fiber optics deliver flawless streams?

The satellite dish is a dinosaur. It’s a one-way communication tool in an interactive world. It blasts a signal to millions, unaware of who is watching. In the age of algorithms where Netflix knows my taste better than my family does, the "spray and pray" method of satellite feels clumsy [7].

The Unshakeable Fortress: Why Nilesat Defies the Odds

If I wrote an obituary for the Arab satellite industry today, I’d be laughed out of the room. Nilesat 201, 301, and the Arabsat fleet are beaming thousands of channels to millions of homes [8]. Why?

The answer is the "Free-to-Air" (FTA) model.

In the West, satellite is expensive. Here, it is free. You buy the receiver once, and you never pay again [9].

"I cannot overstate how powerful 'free' is in an economically stratified region."

When I suggest streaming to my uncle, he looks at me like I’m crazy. "Why pay monthly for what I get for free?" [10] The barrier to entry for streaming—high-speed broadband and a credit card—is too high for many in rural Egypt or North Africa. Satellite doesn't eat your data plan. It doesn't buffer. It just works.

There is also a cultural element. In the Arab home, the TV is a "hearth." In the West, viewing is atomized—everyone on their own iPad. Here, the TV is background noise for the salon, the glue of the evening, especially during Ramadan [11].

Platforms like Shahid are growing, but the collective experience of millions watching *Al Kateeba* simultaneously creates a social resonance streaming can't yet match [12].

The Slow Fade: How the Future Wins

We are entering a long twilight for satellite TV. It won't be a sudden death, but a generational fade. Gen Z and Alpha don't care about the dish; they live on TikTok and vertical video [13]. To them, flipping through 1,000 channels is alien.

As internet infrastructure improves (Starlink, fiber, 5G), the value of the dish will erode. We are already seeing the cracks with the rise of IPTV boxes—the "gateway drug" between satellite and streaming [14].

"I predict that in twenty years, the rooftops of Cairo and Casablanca will look different."

The chaotic forest of rusted metal will slowly be thinned out. But until the internet is as cheap and reliable as oxygen, the classic TV satellite remains the stubborn, unkillable monarch of the Arab media landscape [15].

I will keep my streaming subscription, but I won’t be taking my father’s dish down anytime soon [16].

Sources

- Reference 1

- Reference 2

- Reference 3

- Reference 4

- Reference 5

- Reference 6

- Reference 7

- Reference 8

- Reference 9

- Reference 10

- Reference 11

- Reference 12

- Reference 13

- Reference 14

- Reference 15

- Reference 16

- Reference 17

- Reference 18

- Reference 19

- Reference 20

- Reference 21

- Reference 22

- Reference 23

- Reference 24

- Reference 25

- Reference 26

- Reference 27

- Reference 28